The labour market – where we trade our skills and experience with employers – remains busy. Recent Office for National Statistics data shows net movements of people in the UK from unemployment into employment and from economic inactivity into unemployment[i] A recent poll in England suggested that in the first six months of 2024 19% of employees changed jobs[ii].

Still, there are lots of people who are looking for paid employment. The unemployment rate for people aged 16 years and over was estimated at 4.3% in July to September 2024, and the claimant count was 1.8 million.[iii] At the same time, there are lots of employers who want people with skills they can’t find. One in ten employers have a skill-shortage vacancy, and 36% of all job vacancies are due to skill shortages (according to the Department for Education's Employer Skills Survey[iv]).

The labour market is clearly dynamic. As anyone who has ever tried to move to a new area or work in a different sector will know, it differs depending on where and how you are looking, and the skills, experiences and networks you bring to it. Navigating this market is particularly difficult for some people either due to structural factors (e.g. poor transport and limited local options) or personal issues (skills, health or family circumstances).

Professional career guidance can help all adults as it takes an impartial approach to helping people find opportunities that are right for them. Career guidance can’t on its own make the labour market work perfectly, but it can help make it work better. Career guidance gives people access to relevant job and training information, it builds career management skills that help people make good career decisions, and it signposts or refers people to a wide range of other helpful services. As such it is especially valuable for people who find it difficult to find decent work or make progress in their career.

In England professional career guidance can be accessed through the National Careers Service which has been running in its current form since 2012. However, the Government’s ‘Get Britain Working White Paper’ recently announced that:

In England, bringing Jobcentre Plus together with the National Careers Service will create a greater awareness and focus on skills and careers, as well as genuine collaboration in the decision-making process for current and future skills and careers provision.

How this will work in practice is still being developed.

With our partners from the International Centre for Guidance Studies at the University of Derby we recently concluded a study of what adult career guidance looks like in other countries for the Gatsby Foundation. We chose four countries – Estonia, Finland, Germany and the Netherlands – and explored interesting aspects of practice in a further three – Australia, Belgium and Denmark.

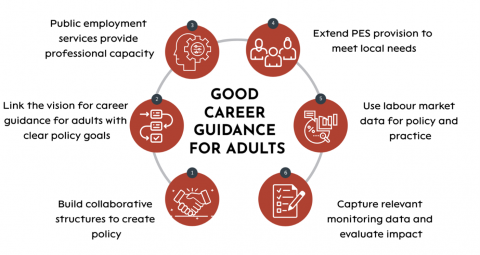

In all four case study countries there is a strong connection between the Public Employment Services (PES) and career guidance services. We found that nowhere has a flawless system and practices in most places are subject to adaptation over time. Nevertheless, their systems did provide good support for both unemployed and some employed people, and a number of features of good practice emerged.

So what lessons can be learned?

Lesson 1: support key stakeholders in collaborative structures that create policy and guide practice.

National policy was informed by experts through regularly convened groups that include all social partners such as local and regional government, academic experts, delivery teams, employers and trades unions. The composition of such groups varies as does the role of government departments within them, but these groups are stable, and part of a regular dialogue with policymakers.

Lesson 2: the vision for the role of career guidance for adults in education and/or economic policy should be clearly articulated in legislation and statutory guidance.

All the four case study countries had policy which set out the role of career guidance for adults. Sometimes this was set within lifelong learning and education policy in which case it emphasised upskilling and reskilling, so for example in one case access to subsidised training was only available to individuals after career advice was taken. In other countries, adult career guidance was part of the suite of policies to promote employment and economic growth. In this case, the effective operation of the labour market drove policy to ensure employers had access to skilled workers, that people were employed, and were able to progress in work.

Lesson 3: Public employment services employ professional career guidance practitioners.

PES are a recognised brand known to people from school education onwards as the place to go for job related support. They can access support from highly qualified PES career advisers (often called career counsellors) were, or other staff such as information specialists. PES offered in-house training and professional development to staff and some offered opportunities to study for accredited qualifications.

Lesson 4: PES services complemented by a range of respected provision nationally and locally can meet the needs of a diverse population.

PES do not meet all career guidance needs alone and extensions of their services included:

- Devolved services that tailor PES services to the needs of local populations delivered alongside local partners

- Co-delivery in community settings (Where PES advisers would work alongside vocational education and training advisers in colleges or libraries)

- Commissioning services that collaborate with, but are delivered separately from PES services (for example, to meet the needs of specific communities such as migrants, people made redundant, or former service personnel).

In addition to services run by or with the PES, there were examples of other sources of professional guidance that included an offer by trade unions, occasionally employers and a small market for privately funded career guidance. These different modes of delivery were often used to reach people from different communities, or with specific needs that would not otherwise be able to access good career guidance.

Lesson 5: Labour market data is important because it both informs service planning, and, gives individuals access to accurate information about opportunities available to them.

National and regional labour market data and future trends were used to consider what carer guidance services were needed. Job information relating to current and future opportunities was used by career guidance practitioners with clients. Different data collection tools and interpretation formats were used in different countries including digital and interactive resources for services users.

Lesson 6: Monitoring and evaluation data is important to understand who uses career guidance and how it benefits them.

People who contributed to the research could describe their work and their partnerships in detail, but it was often difficult to find published information about the numbers of advisers, clients and their job or training outcomes. Better evidence would help further the case for good adult career guidance.

As discussions about the merger between the National Careers Service and Jobcentre Plus develop, it makes sense to look to international practice for insight and inspiration.

To read the full summary and the case study evidence please click here.

[i] Office for National Statistics November 2024, Employment in the UK.

[ii] People Management, June 2024 Workforce moving jobs in the next six months.

[iii] Office for National Statistics November 2024 Labour Market Overview.

[iv] Department for Education September 2023 Employer Skills Survey. A skill shortage vacancy is one that is hard to fill due to a lack of skills, qualifications or experience among applicants.