Young people’s involvement in youth activities: the barriers and enablers

By Jo Hutchinson, August 2025

About the research

We know that young people who get involved in organised youth activities (like sports or arts clubs, uniformed groups, and youth clubs) benefit from their involvement – our work on Youth Provision and Life Outcomes demonstrated this. But we also know that not all young people are involved and therefore they miss out. Our research into young people’s participation in youth activities has been published by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS). SQW delivered the research in partnership with UK Youth, supported by a Youth Panel of six young people with lived experience who helped to shape the research and findings.

The research explored who is more or less likely to participate in youth activities, the barriers and enablers that explain this. It also sought to identify ways to increase young people’s participation and satisfaction. We did this through:

- econometric analysis of the Youth Participation Survey, which was answered by a representative sample of nearly 2,000 young people

- follow-up interviews with a sample of 74 young people

- interviews with 16 professionals from the youth sector who represented a range of organisation types and specialisms

- and a review of existing literature.

The research comes at a crucial time when youth provision is contracting almost everywhere (evidenced by a range of research including our own work as part of the Youth Evidence Base. It fits with the Government’s mission to ‘Break Down Barriers to Opportunity’. And it is being used to inform the forthcoming National Youth Strategy.

The findings

In this blog we highlight three key findings from this work:

Number 1: There are clear and stark differences in levels of participation between young people with different combinations of characteristics.

We found young people are less likely to participate in youth groups and clubs as they grow older, but more likely to participate in volunteering. We also found females, young people living in more deprived areas, and those receiving free school meals are less likely to participate in groups and clubs.

Most strikingly, we produced a series of ‘risk profiles’ with an associated level of participation. We found the lowest rate of participation in youth clubs/groups for females aged 16-19, who live in a deprived area and are in receipt of free school meals – just 26% of these young people are estimated to be participating. This compares to around 90% of males and females aged 10-12 in the least deprived areas who are not in receipt of free school meals.

Number 2: Reasons for this are a complex combination of both ‘Practical’ and ‘Attitudinal, psychological and relational explanations.

Practical barriers include availability, time and other commitments, cost and affordability, access and transport, physical accessibility, parental permission, and information accessibility. These are the types of things that, with resource and effort providers of youth activities can (and are) addressing.

Attitudinal, psychological and relational barriers include alignment with interests and preferences, confidence and apprehension, whether environments feel inclusive, welcome and accessible, and wellbeing and safety. The most common reason young people gave for not being involved in youth activities was lack of interest. These reasons are harder to address, and not all young people will want to get involved, but the role of relationship building between young people and youth activity providers is key.

Number 3: Young people suggested a range of ways to reduce barriers and build enablers to broaden participation.

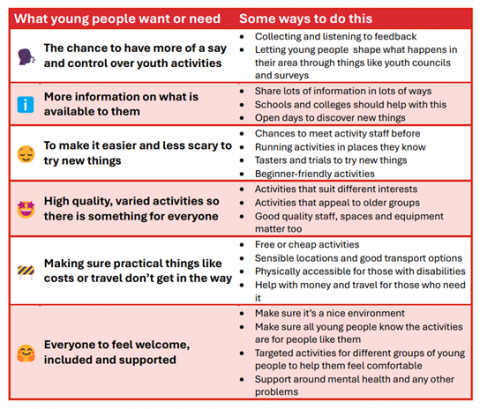

The young people who advised and participated in the research were mostly those who were involved in youth activities and really enjoyed them – they felt more involvement by their peers should be encouraged. They suggested practices to improve participation and satisfaction which we have grouped into six broad areas. These are summarised in the image below taken from the young person-friendly summary of the research.

While these don’t point to any silver bullets, amongst the potential solutions there were some recurring themes: 1) the role of schools and colleges as sources of information and places to have initial interactions with youth providers, 2) opportunities to build relationships with youth workers through access to open days, trials, and tasters that would lower their sense of initial commitment or anxiety sufficiently for them to start and activity, and 3) building voices of young people into plans for activities and services.

Practice implications

There are a range of practical lessons that youth service providers can put in place to help more young people access provision. These include measures such as:

- Prioritise youth voice in service design and delivery and use a range of different instruments to do this from governance to feedback surveys

- Make it fun with a varied, appealing and high quality offer of youth activities

- Make provision visible to young people and their parents and use different communication tools for each. Young people may find things on social media, but traditional media such as posters and leaflets available in school are also valuable.

- Make initial engagement feel easier through tasters and outreach and remove or reduce practical barriers, including considering direct and hidden costs of participation

- Adapt physical spaces so that they are inclusive, welcoming, accessible and supportive environments.

Collectively these adaptations require resource from organisations and trained professionals that are stretched to their limits. Structural issues for the youth sector that include a shrinking workforce, fewer dedicated youth spaces and few investors or investment opportunities provide the context for creating opportunities that young people can engage with. In the meantime however, young people can still be encouraged to learn about youth activities and give them a go to add enjoyment and new experiences to their lives.